I love Japan. I love the culture, the people, the food, the countryside. Our annual trip to this seemingly magical place has become one of the highlights of my year. From the primary root of a language based upon an entirely different set of characters to those used in the West, to the intricate web of social hierarchy and interaction, from clothing styles to music, car design to self-opening and flushing toilets… Japan is perhaps the one place on earth that, despite over a decade of travel, still to me feels truly foreign. It is absolutely unique. Down to the smallest detail.

In Yokkaichi there is a small McDonalds at the train station. We make a point to visit at least once a year. You may ask why, when one finds oneself in a country responsible for some of the most beautiful, fresh and incredible tasting food in the world, we should choose to avail ourselves to this most Western of mass-produced muck. But the answer is that what is produced is, as far as I’ve experienced, the most beautifully crafted piece of muck on earth.

The concept of fast food simply doesn’t exist in a Japanese McDonalds. On opening the cardboard container you are met with a perfect likeness of the image of the burger that adorns the illuminated menu above the counter. Piping hot and meticulously prepared just for you, it’s a Big Mac. But it’s the best damn Big Mac you’ve ever tasted.

This pursuit of perfection, or Kaizen as it is referred to in Japan, lies at the very heart of the culture of this tremendous country. It is a guiding life principle. And it is as true in an individual’s personal pursuit of betterment as it is in business. In the workplace, Kaizen is about learning and using experience to continuously improve process and to strive for a never-ending stream of enhancement in the end product.

The concept, though, has major drawbacks. For to assume that one can continuously improve, suggests that one must constantly consider changing the very foundations of what is already established. Kaizen, as taught by Taiichi Ohno, is all about changing the way things are. So to do Kaizen continuously, one must set a standard, and then change the way in which one goes about achieving that standard in order to improve the end result.

Of course, this will lead to countless mistakes. It is a messy concept, because failure is integral to its path and every bit as important as success. For in failure one learns. Without failure one cannot understand and one cannot improve. As such, Kaizen rests hand in hand with another core Japanese life principle, that of Hansei – self reflection. Humility is key to the betterment of the ideal, as only through trial, error and self reflection can one truly find the path to perfection.

As I took another bite of that beautifully prepared burger in Yokkaichi on the Monday after the 2015 Japanese Grand Prix, the ideas of Kaizen and Hansei played heavily on my mind after what had been an inglorious weekend suffered by Honda at what should have been their triumphant return to Formula 1 on home soil. The posters for the race had featured the RA272 in which Richie Ginther had won Honda’s first F1 race and the all-conquering McLaren Honda MP4/4 in which Senna and Prost had dominated the 1988 season. With such a past, Honda’s great return was the most almighty disappointment. That 12th and 14th on the grid seemed like a success was indicative of the trouble in which McLaren and Honda have found themselves this year. In the race itself, Jenson Button found himself being overtaken for position as though he was being lapped, and Fernando Alonso slammed his power unit as being like a “GP2 engine,” before letting out a pained, raw, animalistic scream.

It was an embarrassment.

The thing is, Honda will get it right. There is quite simply no way that it won’t. Honda has not simply forgotten how to make engines. And, due in equal part to Kaizen and Hansei, when Honda does get it right, because they will have failed so desperately along the way, they will perhaps understand the concept better than anyone, and produce a better end product than anyone. That same pursuit of perfection will, ultimately, produce the results they seek.

How long McLaren is willing to wait, or indeed how long their drivers will be prepared to wait, is another matter.

Thoughts of Kaizen and Hansei and the concept of success through failure, while noble, lies in direct contrast to the prevailing Western trend of immediate success. How different a world we live in where one’s sole focus is the end product, rather than the Japanese focus on the path to achieving said aim. How different, I thought, the approach from Honda to that of Red Bull. For the four-time champions there was no introspection, no decision to work with an engine partner through failure to find the path to perfection. Instead, the sole focus was on the end product. If that which they have was not good enough, it must be swapped for another. No effort to fix or improve what exists. Reflective perhaps of the throw-away nature of Western culture, replace what does not work with something new. Can this process ever lead to perfection? Perhaps not, according to Japanese culture.

Honda has a long road to tread to achieve success however. For at the heart of Japanese culture lies the concept of respect and hierarchy. Much was been made of the difference in methodology between East and West in the collapse of the works teams from both Honda and Toyota in Formula 1. And the same issues which stopped those teams from achieving success as manufacturers, may yet hamper Honda’s development.

Harmony within a group, or Wa, relies upon the acceptance of co-operation and that each person within the infrastructure of a hierarchy understand their role and position. When this is achieved, the whole group benefits. Decisions take longer because consultation of all those within the group is an intrinsic part of Wa. That doesn’t mean that consensus requires unanimity, but consultative decision-making is deemed crucial in order to ensure effective information exchange, reinforcement of group-identity and thus a smoother implementation of the decision.

Much of this is due to the fact that the very concept of social order in Japan has, at its roots, the Confucian theory which became part of the prevailing Chinese influence on cultural changes that affected Japan in the sixth Century. Confucianism preaches harmony between heaven and earth, humans and nature, via an acceptance of one’s role within a given society and the promotion of social order by proper behavior. It’s why the Japanese find a lack of behavior or conduct unbecoming of someone’s position within a hierarchy to be so awkward.

In Japan, order within companies and organisations is often referred to as “diffuse order,” because responsibility is collective precisely due to this group decision making. The leader of the group is as much part of the group as his apparent subordinates and this is a key factor in weakening the concept of leadership as we might think of it. Leadership in this sense does not call for strong and forceful management and instinctive decision-making, but for tact and sensitivity. A mixture of Giri (duty) and Ninjo (compassion) are the hallmarks of a good leader in Japanese businesses.

And yet, in spite of the collective decision-making and diffuse order, leaders are still expected to assume responsibility for any shortfallings of the group. Even if they have had no direct involvement in the unfolding situation, they may still be required by convention to resign their position should the failure be great enough to merit such.

One wonders how long Arai-San can hold on.

But one must also question the actions of certain individuals within the hierarchy and the role they are playing. In particular, Fernando Alonso.

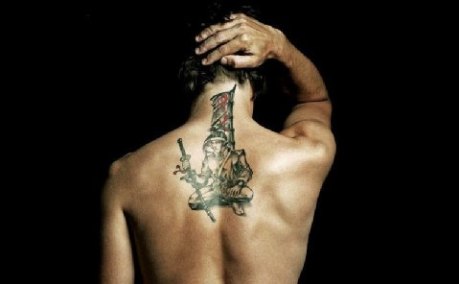

Alonso himself has claimed many times to be a student of Japanese teachings, in particular Bushido, the way of the warrior, and has stated that he is inspired by Hagakure, Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s 18th Century spiritual guide for the warrior.

Bushido itself is the code of the Samurai, and in the Western world is a concept we would most closely align, perhaps, with chivalry. “The way” originated from Samurai moral values and is an unwritten and unspoken code, which had to be mastered in order to become Samurai. It revolves around eight values: those of righteousness, courage, benevolence, respect, sincerity, honour, loyalty and self-control. At least three of which, the two-time world champion let slip during his outbursts in Suzuka.

Alonso has a tattoo on his back of an ancient Samurai, and after the Malaysian Grand Prix this year told Marca “My tattoo is a way for me to remember who I am, where I come from and the strength I possess. The Samurai take everything to another level: one must fight, things don’t just happen. It also reminds me of something important that happened to me: the Samurai in the drawing is kneeling, almost in defeat, but always looking up.”

The Hagakure, the teachings upon which Alonso claims his tattoo is based, provide many transferable passages which the Spaniard might do well to remember in his current difficulties. Maybe one of the most relevant is the following:

“There is something to be learned from the rainstorm. When meeting with a sudden shower, you try not to get wet and run quickly along the road. But doing such things as passing under the eaves of houses, you still get wet. When you are resolved from the beginning, you will not be perplexed, though you will still get the same soaking. This understanding extends to everything.”

Is Alonso, then, a Samurai as he might like to think? His public outbursts of late are not the actions of the chivalrous warrior under Bushido. What, then, is he? A Shinobi? Certainly his actions in the spygate scandal of 2007 would lend themselves to those of the covert assassins of Japan’s feudal age.

Perhaps, a Ronin. A Samurai with no lord or master. With Flavio Briatore banned from the sport, is Alonso a warrior forced to walk alone due to the shame placed upon his former master and as such, an aimless, wandering sword for hire? Is his path one of an avenger as the Japanese legend of the 47 Ronin? Or has his public admonishment of his superiors disgraced him enough to lead him to walk the path of the vagrant and become Ronin by his own actions?

The Hagakure states that “it is unthinkable to be disturbed at something like being a Ronin. People used to say, ‘If one has not been a Ronin at least seven times, he will not be a true retainer (Samurai.) Seven times down, eight times up.”

Perhaps this is the line Alonso cares to treat most favourably of the teachings contained within the pages of Hagakure. For that, he may like to think of himself as Samurai. But for his courage, he seemingly falls short.

Perhaps that’s why the team needed Jenson Button on board again in 2016. As the 2009 world champion stated after the Japanese Grand Prix, he felt “like a Samurai warrior without his armour and sword.”

Defenceless, perhaps. But honorable.

Postscript:

The following was written as a comment on Reddit by Santiago Paz, who alerted me to his words via twitter. I really loved the continuation of the theme, and so I include them here for everyone to enjoy:

“I come from a city in Peru called Arequipa, which lies right next to a volcano. And we say “not in vain, we are born at the feet of a volcano”. We are strong headed and short tempered. And that costs us a lot, sometimes. Nando has the raw will to come through all dificulties. But his hot head plays against him sometimes. In this case I belive that he is voicing his thoughts on the radio to bring shame to Honda on purpose. Because he wants them to see that the current version of the approach is dead wrong. Because maybe he knows that the current management is doing things WRONG. And due to the corporate culture, no one below Arai can question that. So the only one who can stand up and fight for those unable to voice her concerns is NANDO. So he’s doing what we can, without angering Ron or his fans. The weak spot in this is that we all know that he only wants to win, as any other F1 driver. So thinking he’s being the defender of those who can’t talk is a bit romantic. But I like to think that, much like a certain type of Ronin, he brings shame to himself, in order to do right to others around him. Truly honorable”

So very well written Will. D X

Sent from my iPhone

>

Another great piece Will. in a time of limitless choice, I will always make time to read your blogs. Well researched, poignant and well edited. Keep up the great work.

Brilliantly written!

Loved the article, specially the final words. 😀

While we’re quoting Ghost Dog, “the end is important in all things”.

Well done.

Will – You always leave me wanting more…..write a book!

Will, thank you. Thoroughly instructive. The spirit Alonso proclaims should run deeper than the surface expression of a tattoo. Quite disconcerting is this “warrior” so publicly lowering his “mask” and airing grievances. No Samurai spirit there. Even a Shinobi uses silence as a means to an end, being highly adept in the art of stealth. Team mate Button’s disciplined temperament offers Fenando an up-close tutorial on “The Way”.

Pretentious ballocks.

Think you’ll find it’s “bollocks”

Thanks Will …

Great post. Great research, well written, excellent story. Thank you Will

Nicely written as always…

But will Fernando Alonso’s “teachings” have any effect on the Japanese Corporate Culture?

Nice article but I would like to respectfully disagree.

1. First time around, Honda got lucky with their one win; second time around, there really wasn’t that much competition (mostly DFVs, and in the season everyone talks about only Ferrari was also running turbos); third time around, when there was a sustained level of competition, they were an ABJECT FAILURE, despite having the biggest or second biggest budget on the grid.

2. For anyone who has spent any length of time working with the Japanese, you will know that they are far far too arrogant to believe that any gaejin could possibly know more than they… This they are not open to outside/new ideas and thus not willing to invest in the best possible team to take them forward. Even Ferrari, 30 years ago, realized this. Will, you mention in detail the Japanese culture, but don’t take your argument nearly far enough. IMO, this is indeed why Fernando I slashing out in the most public way; it can be truly soul-crushing working in this resolutely obstinate culture.

CTP, Will’s thesis is spot on. Your displeasure needs amending. So many other Honda power-plant attributes could be cited but, for here and now, consider this bit of race trivia: At the US’s INDY 500, 4 years in a row, up to 2009, all 33 cars on the grid had Honda engines, and for those 4 years there was not a single engine failure. The Japanese have not become a modern-day power by being closed to outside/new ideas, as you put it. Quite the opposite. They have adopted and adapted admirably, perhaps more so than any culture that has had attempted to adapt and adopt to outside theories and influences.

As a “gaijin” who has spent much resident time in Japan and has Japanese relatives, I am supposing that a lot – if not most – of the obstinacy you reference flowed in the opposite direction – and not from the Japanese towards you. Us foreigners, particularly from the “advanced” West, often want all perceived-as-lesser cultures to be awed by our presence and offerings instead of simply observing and learning and accepting. If you have ever lived there, Japan has done more for you that you are generous enough to acknowledge. For its size and other inherent disadvantages, Japan has little else to rely on other than an admirable work ethic and sheer determination, rather than the arrogance you claim. Alonso, lashing out in public, is a stark opposite to team mate Button whose resilience and calm under immense pressure parallel the winning characteristics of the Japanese.

Guarantee: the current McLaren hardships shall pass. Honda’s Japanese-ness will have it no other way

Beautifully written Will, but I see Fernando’s outburst closer to pure frustration of wanting to do well on Honda’s turf, but impossible for him to do so. As in an earlier post, it might have something to do with Japanese arrogance. Let’s look at the two top manufacturers from Japan, Toyota and Honda. Both make terrific cars, but both have lost huge ground to the competitors from Korea. Why? IMO, they stopped going with Western ideals of what makes a good looking car. They struck out in odd directions, producing some truly ugly cars, and in the case of Honda, sticking with smaller motors and front wheel drive, when the world is going for more power and rear wheel or all wheel drive. With such a huge fan base, why have Japanese drivers had so much difficulty in reaching the higher rungs of the sport? Is this arrogance, forcing dangerous mistakes without the skill to back it up, or does their system keep those with the best potential from reaching the top and allows those with more money or influence to reach F1? I’m not sure, but it seems to me they are doing some things very, very wrong.

As much as I think Honda can do very well, I wouldn’t necessarily agree that it is inevitable. Their last foray in F1 was Pretty poor, and only came good once Ross Brawn was allowed to get on with things rather than running everything past his Japanese colleagues. That said, that was running the whole team rather than just creating an engine so maybe it isn’t the same comparison.